“Does the science in science fiction have to be accurate?”

That’s a question I’ve seen more than once. But beyond the (debatable) basics, what does “accurate” even mean in terms of science fiction?

When I was a kid, an astronaut came to my elementary school. The thing I remember most vividly is his rundown of all the reasons why a mission to Mars was and would always be impossible. It was basically a list of all the ways in which humans would die before even touching down.

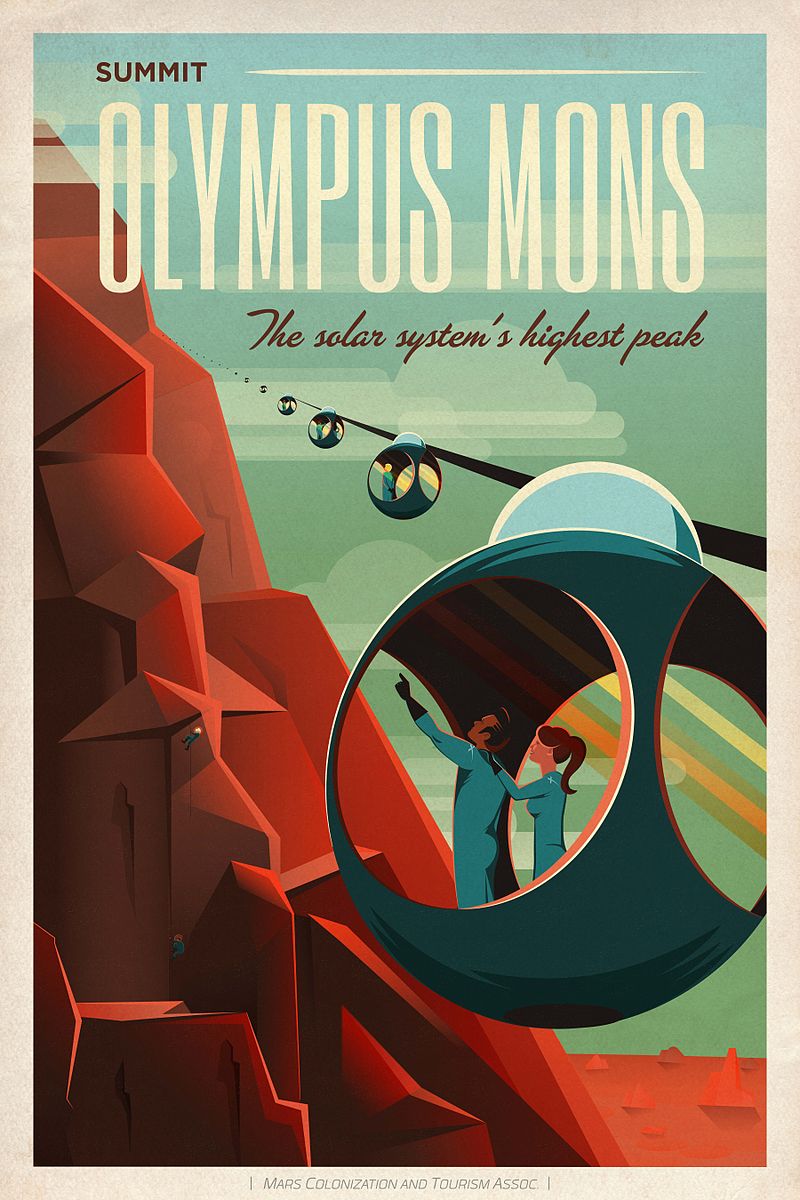

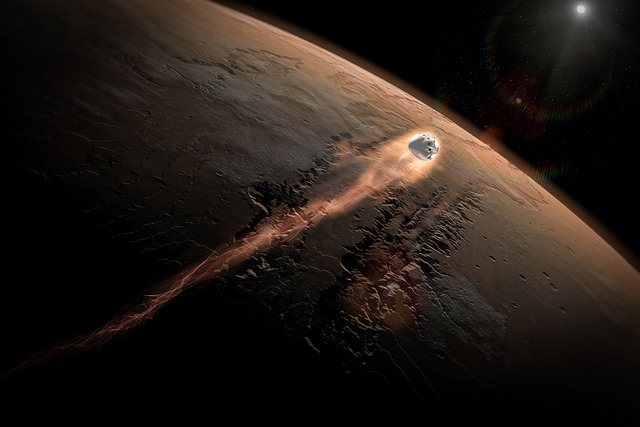

But now a lot of people–including experts–seem convinced that a Mars mission is right around the corner. And maybe it is. Or at least, it’s not impossible.

In the early 90s, people were talking about the internet. But what did people think was the technology of tomorrow? Virtual reality. We were definitely heading for the cyberpunk future that we saw in novels and comic books, the future that mashed together wired, dial-up internet access with VR. VR as a way of life seemed inevitable.

Then access to the web exploded, wifi happened, smartphones happened, and it’s really only been in the last few years that VR has come back into the conversation. We weren’t on the path we thought we were on at all.

I like hard sf, I like science, and I appreciate it when authors do research.

But.

When we rely on a projection of current science in order to create imaginary future science, we sell ourselves short.

Over the last few years, I’ve sat through several convention panels on hard sf and science in sf. Lots of the content has been great, buuut sometimes I find myself gritting my teeth. Particularly when the panelists return over and over to the idea that x or y is impossible forever because it’s impossible now.

And then there’s the judginess: This book is idiotic because they didn’t even try to explain what powers their space freighter. This story is contemptible because there’s no detailed explanation of their FTL technology. This series makes no sense due to the fact that X cannot be Z without Y, because we know that Q is required for Y and Q can never exist. Never! Because that’s how we understand it right now. (Never mind that the QXYZ field was purely philosophical till 1950 and purely theoretical till 1990.)

This is a bizarre attitude for science fiction writers or readers.

When my mother graduated from high school, she hadn’t learned anything about plate tectonics. In fact, the idea that the earth wasn’t solid would have sounded completely unhinged to members of the general public for the first half of the 20th century.

When I graduated from university, I didn’t know that Neanderthals and humans had interbred, let alone that I have 287 Neanderthal genetic variants in my own DNA.

In the year that I got my first job, a lot of geeks were sure that an incredible new invention was just about to revolutionize our society. It turned out to be the Segway. (Sad trombone.)

We are not terribly good at predicting what’s on the next page, let alone the next chapter. If we keep our imaginations trapped in the book of what we know now, what’s the point?

I’m not saying we should throw our hands up and make handwavium the order of the day. But we can at least acknowledge the blinders of history and our position in it. It’s OK for science fiction stories to be based on technology that wouldn’t be possible without a major change in our understanding of the universe. In fact, it’s more than OK.

We have radical discoveries yet to come. In physics, in medicine, in mathematics, in biology, in cognitive science — and in fields for which we don’t even have names yet.

So go ahead. Dream up something so big, so inconceivable, so different that it’s not even a glimmer on the horizon. Dream up something that would require a whole series of radical discoveries. You’re going to be wrong about what the discoveries are, and even more wrong about their repercussions. And…that’s fine.

Because things will change. We don’t know how yet–and that’s the good part.