J[onathan] T[ownley] Crane’s book Popular Amusements was published in 1869. As you might guess (or maybe you can figure out from the teaser in my last post, or from the title of this one), the answer to the question “What popular amusements does Crane suggest?” is “NO!” Base ball (sic)? It’ll kill you dead. Dancing? Kill you dead. Chess? Kill you dead. Cards? Kill you dead. Theater? Kill you dead. You begin to see the pattern. You suggest any possible fun thing to do, and JT will tell you why it will kill you. Crane really could have saved himself a lot of time by using a much bigger font and just having “DON’T DO IT!” written across the inside of the covers of an otherwise-empty book. But here’s the odd thing. JT Crane actually gets that taking a break from work to play will actually make people do better work and live longer. It’s just that, basically, if it’s a fun sort of playing, it will kill you dead. On the other hand, not taking a break every so often? Kill you dead. You can’t win in Crane’s world, I guess.

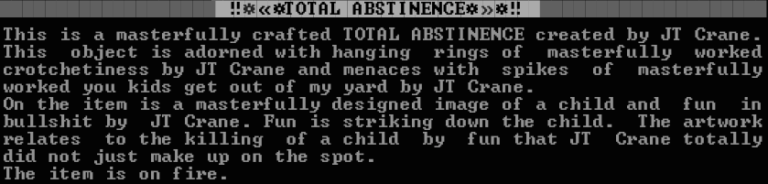

Crane spends quite a few pages on novels, “one of the great vices of our age.” The problem? People are reading too many novels and kids these days don’t read anything else. Oh, and also most of the novels are evil. Crane admits that there may be a few okay novels, but the vast majority of writers “exhibit results of every degree of badness.” Crane finds the situation so dire that he endorses not just total abstinence but TOTAL ABSTINENCE. I suspect he meant to say ‼☼«☼TOTAL ABSTINENCE☼»☼‼1, but this being 1869 his editor couldn’t make sense of it since he had never played Dwarf Fortress.2

But to his credit, JT Crane was actually much smarter than abstinence-only folks today. He knew abstinence–only programs don’t work, so he offers some guidelines to keep non-abstaining novel readers safe.

Guideline 1: “If you have but little time for reading, spend none of it on works of fiction.” What do you read instead? “Read your Bibles.” So, some of us have different definitions for fiction. JT continues. “Read history, the records of the past, and the accounts of current events.” I’ve read histories from the 1700s and 1800s, and I’d be careful about shelving them too far from fiction. Yes, some people were trying to collect and interpret evidence, but I don’t think I’m being unfair when I say that the bulk of the historians whose works JT would have recommended weren’t overly concerned with things like evidence. “Read the biographies of good men and women.” Yeah, those couldn’t possibly involve wild flights of fancy unhindered by silly things like truth or reality. “Read books of science.” In the 1860s, the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London was publishing things like “Contributions towards Determining the Weight of the Brain in Different Races of Man” and “On the Brain of a Bushwoman; And on the Brains of Two Idiots of European Descent.” And this was after they and raised the standard for membership to require some sort of actual scientific street cred. Now, to be fair, there were a lot of good things being written and published in the 1860s. I just want to point out how much glass JT has built his house out of, and to suggest that he not finish that potato cannon he thinks he has concealed in a glass cabinet in his glass bathroom.

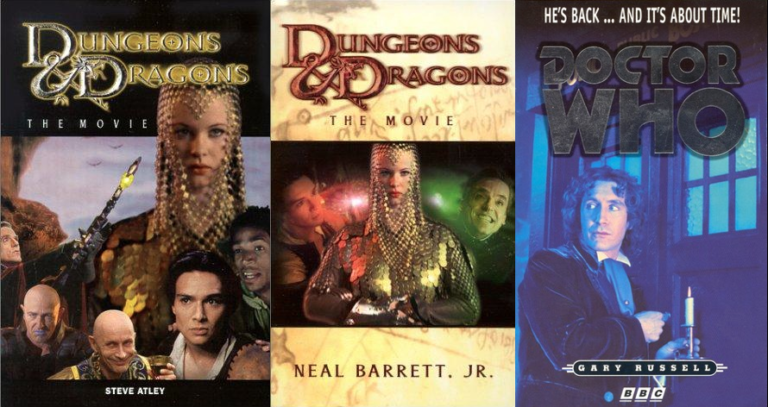

Guideline 2: “In any case read only the best works of fiction.” Oh, word? Thanks, JT. I’ll just cross the novelization of the Dungeons & Dragons movie off my to-read list.

http://openlibrary.org/isbn/0786914394

http://openlibrary.org/isbn/0786917857

http://openlibrary.org/isbn/0563380004

Guideline 3: “In all cases let works of fiction form but a very small part of what you read.” What does this mean? It means “read ten good, substantial works to every one of fiction, however good.” So even the best fiction will never count as a good substantial work. This makes sense if, as I mentioned in the last installation of this series, you assume that these people lived in the Ars Magica universe and that spending three months reading a book about, say, carpentry was a better way to level up your carpentry skill than actually spending three months working as a carpenter.

Guideline 4: “Cease wholly to read fiction the moment you find that it begins to render substantial reading distasteful, and the common duties of life irksome, or injure you in any way in mind or morals.” This advice is charmingly vague; the only solid thing in it is the assumption that there is some amount of fiction that you can read that will render substantial reading distasteful, the common duties of life irksome, and injure your mind or morals. In fact, if we assume that there exists an amount of anything that could render doing things distasteful, the common duties of life irksome, and injure your mind or morals, then this could work for pretty much everything in life, not just fiction and “substantial works.” Let’s try it. “Cease wholly to read advice books by peevers the moment you find that it begins to render all reading distasteful, and the common duties of life irksome, or injure you in any way in mind or morals.” Really, though, deep vein thrombosis seems a more pressing danger of excessive reading than — nah, I’ll spare you the whole “rendering substantial reading distasteful, the common duties of life irksome, and injuring your mind or morals” thing this time. Oh, sorry.

Actually, though, Crane gives this advice because he doesn’t see the difference between The Count of Monte Cristo and crack cocaine. He dedicates almost three full pages to Guideline 4, and all three are about addiction. Just like Dr. James Baldwin, JT Crane wants us to know that novels are actually, literally, medically addictive.

In case you need help convincing people to either adopt a TOTAL ABSTINENCE policy (or is that POLICY?) or, at the very least, follow Crane’s four guidelines, he also offers seven convincing reasons that novels are dangerous. Oddly enough, peer-reviewed double-blind clinical trials on their addictive qualities is not among the seven.

Convincing Reason 1: “It wastes precious time.” Crane informs us that by “universal consent,” works of fiction are called “light literature.” As you will see when we get to The Kids These Days and The Dancing, Crane has a rather unique take on the word “universal,” by which he means “everybody in the world excluding all of those people who don’t think so.” Crane also has an interesting definition of “light,” by which he apparently means “written by people who are moral and intellectual light-weights.” Real thinkers – excuse me – REAL THINKERS apparently write non-fiction, and the kids these days (yes, he is specifically worried about the kids these days) should be suffering through real books rather than enjoying fiction. I guess JT and Dr. Baldwin wouldn’t see eye to eye on the value of textbooks.

Convincing Reason 2: “Excessive light reading injures the mind.” This is the point he was making in Convincing Reason 1, but now he also says that when you read novels, you “simply witness the action, and watch the unfolding of the plot.” Wait, isn’t that what people are saying about television, movies, and video games? Also, JT assures us that people skip all the good, educational, or eloquent bits in novels because they read too darned fast. As you may recall, John Ruskin also warned us about the dangers of paying attention to the plot in his 1857 work, The Elements of Drawing. Sorry, JT, but Ruskin got there before you. I was going to say “got there first,” but I’m sure some other silly folks were saying this before 1857.

Convincing Reason 3: “Excessive light reading tends to unfit for real life.” (Ed. note: apparently “unfit” is a verb.) In other words, Crane has noticed that people who read novels are less likely to be content with their horrible real lives. As someone whose career depends on making people be content with their horrible real lives, this is something Crane just cannot tolerate. “Works of fiction would be less doubtful reading if the reader, after finishing the last page of the story, utterly forgot the whole, or remembered it only as we remember veritable history.” Hold up a minute. Wasn’t Crane just complaining about how people read too darned fast and miss most of the novel? Don’t worry, this sort of contradiction is pretty normal when people complain about the kids these days. Also, it sounds like Crane is saying that people don’t actually remember the history they read all that well. In fact, it sounds to me like Crane is actually implying that novels are substantially easier and more pleasant to read than something like Blackstone’s Commentaries on the Laws of England. I’m not sure that’s a fair comparison. I mean, from what I’ve read, Commentaries on the Laws of England is a surprisingly easy read for a four-volume law book from the 18th century, but it’s also a four-volume law book from the 18th century. Novels are hardly the only entry on the list of things most people would find more interesting than Commentaries on the Laws of England, so while Crane may not be wrong, he’s also not particularly useful here. And Commentaries is noted for being unusually well-written, clear, and enjoyable. The list of things most people would find more interesting than the atrocious now-public-domain translation of Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics that I’m currently suffering through includes things like “setting up the board for Axis & Allies while blindfolded and covered in fire ants,” “talking to your racist friend about Black Lives Matter,” and “having to think of a third unpleasant thing that could be on the list of things people would find more interesting than the atrocious now-public-domain translation of Nicomachean Ethics that I’m currently suffering through.” Essentially, though, Crane’s complaint is that novels are not unpleasant to read, while most of the things he wants people to read are. Sounds a lot like Ruskin’s costermonger, really. Ruskin introduced us to the costermonger who, after enjoying authors like Dante, is unwilling to return to a life of drudgery in his 1964 lecture “Traffic,” beating Crane to the punch by five years.

Convincing Reason 4: “Excessive novel-reading creates an overgrowth of the passions.” Crane is sure that readers will be unable to tell fact from fiction, and eventually come to believe that they are characters in the novels they read. They will lose touch with the awful 19th-century reality in which they live and escape into those novels. I’d love to be able to say that I can’t imagine anyone being foolish enough to actually believe this is an issue, but then I think about how people react to video games, television, movies, and role-playing games. I’m also fairly sure that Crane isn’t the first person to make this claim about novels. Clara Reeve comes to mind, and she made her point almost a century before our boy JT.

Convincing Reason 5: “The habit of novel-reading creates a morbid love of excitement somewhat akin to the imperious thirst of the inebriate.” I’m still waiting for the double-blind clinical trials on this one. Okay, to be fair, Crane had no idea what crack cocaine was, but he does compare novels to opium. This is such a common claim that I’m running out of funny things to say about it.

Convincing Reason 6: “The habitual reading of novels tends to lessen the reader’s horror of crime and wickedness.” I’m really confused here. That’s twice that I’ve thought we were talking about video games. Whatever. Crane has two points to make here. First, people rarely commit crimes before they have been made to think about crimes a lot. In other words, people don’t kill people. Novels do.

Crane’s second point for Convincing Reason 6 is that “books are sometimes written to serve a special purpose.” As you might guess, the “special purpose” is to spread evil. I didn’t think that JT Crane had ever heard of the works of Ted Beale. But joking aside, this is actually a real issue. I’m pretty sure I’ve just read a book written by an angry, unstable doofus who wanted to push his wacky ideas onto everyone. What was it called? Popular something? I’m blanking.

Also, apparently novels can lead to suicide. Crane even “quotes” a “suicide note” that he found in a religious periodical that just happened to come to hand while he was writing. The writing is so over-the-top that I can only assume it is fake. Also, “Here is a totally true and authentic confession/suicide note from someone engaged in a harmless activity that I happen to despise that I somehow just stumbled onto and didn’t at all hastily throw together because I needed something sensational!” is sort of a trope for people who write absurd things like Popular Amusements.

I believe that if I had never read a novel I should now be on the high road to fortune; but, alas! I was allowed to read the vilest kind of novels when I was eight or nine years old. If good books had been furnished me, and no bad ones, I should have read the good books with the same zest that I did the bad. Persuade all persons over whom you have any influence not to read novels.

It’s good to know that the people who write infomercials and letters to Penthouse were able to find work as far back as the late 1860s.

Convincing Reason 7: “Excessive devotion to fictitious reading is totally at variance with Scriptural piety.” Crane says “This needs neither proof nor illustration,” and while he provides the latter, he sticks to his principles and doesn’t provide even a hint of the former. This is extra amusing when you compare the Methodist Episcopal style of worship to Matthew 6:6. Maybe we need to add “Scriptural piety” to the list of things that don’t mean what Crane thinks they mean.

While Crane doesn’t think it necessary to explain how novels conflict with Scriptural piety, he apparently realizes that he can’t just get away with saying “I don’t need to prove or explain Convincing Reason 7, so on to Convincing Reason 8!” My original suspicion was that he realized not illustrating or proving a point that he said didn’t need illustration or proof would dishonestly imply that he was actually paying attention to anything he wrote. Then I figured that he couldn’t think of more than seven Convincing Reasons, which is pretty sad when you actually count them up and only get five. That doesn’t make sense, though. I mean, look at page 151 and imagine that he just stopped writing after “This needs neither proof nor illustration.” The whole rest of the page would be blank, and that’s how the chapter on the danger of novels would end. I’m pretty sure Crane wasn’t being paid by the word, so the only reason I can think of is that he considered a mic drop to be more dangerous than a novel.

What did Crane write about rather than dealing with Convincing Reason 7 or thinking of a Convincing Reason 8? Well, basically, he just summarized his first four Convincing Reasons all over again, almost as though he realized that his first time explaining them wasn’t particularly convincing. I think Crane’s blood sugar may have been low when he wrote this one, and I don’t need to prove or illustrate that statement.

| Stock Attack | Used? |

|---|---|

| Stimulation of violence, sadism, and criminality | ✅ |

| Undermining of sexual morality and legitimate authority | ❌ |

| Promotion of passivity through narcotization, hypnosis, and desensitization | ✅ |

| Substitution of fantasy for reality; promotion of escapism | ✅ |

| Promotion of stereotypy, distortion, oversimplification, and irrelevance | ✅ |

| Deliberate emotional manipulation and exploitation of consumers | ❌ |

| Destruction of literacy | ❌ |

| Weakening of family ties | ❌ |

| Destruction of artistic integrity and creativity in society | ❌ |

| Homogenization of culture at the lowest level | ❌ |

| Promotion of materialism and conformity | ❌ |

| Making readers less intelligent | ✅ |

| Posing an actual physical risk to health | ✅ |

| Being addictive in the same way that drugs or alcohol are | ✅ |

| Being metaphorically (or literally) infectious, toxic, or venomous | ✅ |

| Causing the end of some mythical golden age, or at least reminding us of its end | ❌ |

| Being fun or pleasant, since nothing fun or pleasant can be good for you | ❌ |

| Total: | 8 |

JT got a score of 8! Not bad! You might think I should have given him one for “Being fun or pleasant, since nothing fun or pleasant can be good for you,” but that isn’t quite true. As I mentioned at the start of this article, Crane does take a few paragraphs of Popular Amusementsto talk about just how important recreation is. JT wasn’t opposed to fun itself. He was just opposed to the enjoyable kind of fun.

Finally, I’m sure JT Crane would like me to remind you that the only 100% reliable method for avoiding moral corruption is TOTAL ABSTINENCE FROM NOVEL-READING HENCEFORTH AND FOREVER. And he’d want it done like this:

Next time, we’ll look at more people who can’t really tell the difference between books and dangerous drugs. The difference is that some of these people are still alive today. Specifically, we’re going to examine the unreasonable fear of romance novels.

1: ☼TOTAL ABSTINENCE☼ is a masterfully crafted TOTAL ABSTINENCE, the ☼« and »☼ indicate that it is masterfully decorated, and the ‼ ‼ indicate that it is also on fire.

2: Being 1869 was also the only reason that playing Dwarf Fortress wasn’t topping the list of things that will kill you dead.