JT Crane isn’t alone in comparing novels to drugs. I was browsing merrycoz.org, which is where I’ve found a lot of the characters I’ve written about, when I found a couple of articles written by F. C. W. (quite possibly Francis C. Woodworth) published in The Mother’s Magazine, . In “Moral Poisons: The Antidote,” F. C. W. not only compares books to arsenic, but he also includes one of those charmingly fake notes from someone who was hopelessly addicted to novels. Let’s see what’s going on with this guy.

It turns out this F. C. W. wrote a number of articles on the dangers of novels and reading in The Mother’s Magazine. We’ve got

- “Moral Poisons,” November 1842

- “Moral Poisons” (yes, again), February 1844

- “Who Write Our Novels?,” September 1844

- “Moral Poisons: The Antidote,” May 1845

- “Moral Poisons: The Antidote” (yes, again again), June 1845.

- “Vicious Novels: Cause of Their Increase,” December 1845

This F. C. W. character has written one or two innocuous pieces for The Mother’s Magazine, so they aren’t just a crank who sends in a weekly rant that gets published whenever the editors run out of reasonable things to print. But who is F. C. W.? According to Pat Pflieger at merrycoz.org (who is an academic and actually studies stuff like this, rather than just being some Internet rando like me), F. C. W. may very well be Francis Channing Woodworth, a printer, preacher, writer, and editor. He specifically wrote literature for children, and he edited Woodworth’s Youth’s Cabinet, a magazine for young children. You can read some of them on archive.org. The magazine is a lot like modern magazines for children, filled with puzzles, poems, pictures, brief biographies of famous people, short stories, natural history, and the like. The one linked to starts with a description of Pompeii and is filled with reminders that the citizens of the city were vile creatures who deserved to be wiped out. Also, the author bribes his guide and steals something from the ruins. This, of course, is exactly what I would expect from a guy who claims to be worried that novels are teaching people unethical behavior.

Woodworth also wrote stories for very young children under the pen name “Theodore Thinker.” As Woodworth, he is keen to remind you in every issue of his magazine that he also writes stuff as Thinker. As Thinker, however, he doesn’t mention being Woodworth at all, and instead shamelessly plugs Woodworth’s Youth’s Cabinet as though he wasn’t editing it every month. Here, for example, is what he says in The Holiday Book:

I can tell you what the name of it is, if you would like to know. It is Woodworth’s Youth’s Cabinet, a magazine made on purpose for children. The day before that on which Frank and Susan made the visit to the old chestnut-tree, in the sheep pasture, where they are represented in the picture, their father came up from New York, and brought them one of these magazines, telling them that he was going to have a new one sent to them every month.

They found a great many things in this magazine which pleased them very much. The stories, the little pieces of poetry, the scraps of history, and the descriptions of wonderful things, delighted them so, that they could hardly take their eyes off from the book until they had read it through.

The Holiday Book is also casually racist in exactly the way you would expect from a 19th century book designed to develop children’s intellects and morals. Clearly, Woodworth is one classy guy, and exactly the type of person who would write multiple editorials entitled “Moral Poisons” for The Mother’s Magazine.

What did F. C. W. say in these editorials? In the first “Moral Poisons,” F. C. W. describes walking into a friend’s house and finding two children (both between the ages of fifteen and twenty-one) reading absolutely horrible books: Zanoni, by Edward Bulwer-Lytton, and The Complete Works of Lord Byron, including The Suppressed Poems (possibly this edition, but possibly not). Judging from Woodworth’s Youth’s Cabinet and The Holiday Book, Woodworth writes for young to very young children. I’m not sure how much he knows about people who are well on their way to being adults, or already legally adults, but as we’ve seen several times in this series, not knowing much about a topic absolutely will not stop anybody from writing about how dangerous it is.

Oh! what would become of the rising generation, if all our pious parents thought and acted like these! Is it any wonder that the minds of our youth are so often and in many instances so fatally poisoned, when those who sustain the parental relation introduce such literature into the family circle, and countenance and encourage their children in reading it? Let it not be forgotten that works of the imagination exert a more powerful influence, not unfrequently, for good or for evil, than those of a graver character. How important is it that they should be free from any moral taint. How desirable that they should breathe nothing but virtue and purity. And can it be necessary at this late date to prove to the parent, the affectionate, the devoted, the Christian parent, that Byron and Bulwer, and writers of their school of morals, are unfit companions for his children? Does it need a labored argument to convince Christians that authors of this stamp exhale in the family circle an atmosphere charged with the elements of disease and death?

I don’t want to quote the whole article, but I think F. C. W.’s next 1.5 paragraphs are also pretty good. Here they are.

It is not denied that something may have emanated from the minds of these men suitable to be exposed to the eyes of purity. It may be admitted, even, that they have written some things, which, regarded as specimens of literary taste, are valuable. But both these authors wrote under the influence and in accordance with the promptings of a heart blackened with vice, impurity, and debauchery.

It cannot be supposed that their writings generally should be free from the bias of the mind which gave birth to them; and an examination of their works shows them to be just what might be expected. Few indeed are the poems of the one or the romances of the other, which are not more or less contaminated with immorality; and some of the productions of both are as vile and loathsome as anything in the shape of literature which Satan ever instigated his disciples to compose to subvert his purposes.

“How important is it that they should be free from any moral taint.” Right. I’ll just leave this picture here and you can draw your own conclusions.

I can sort of see why he might object to Byron, since Byron was a fan of the old ![]()

![]()

![]() and wrote about it in terms no less explicit than I just did. He also engaged in quite a lot of it, including (so stories go) with over 200 different women on 200 consecutive nights, at least one or two women married to men who were not Lord Byron, possibly a sister-in-law, and maybe a choirboy. I guess Byron checks all three of F. C. W.’s boxes: a heart blackened with vice ☑, impurity ☑, and debauchery ☑. Why Bulwer-Lytton, though? Sure, he gave us “It was a dark and stormy night,” but that gave us the Bulwer-Lytton Fiction Contest. Also, he may be in part responsible for the fact that formal wear for men is typically black in the US and UK. But are purple prose and black tuxedoes really enough to condemn Bulwer-Lytton? Well, he might also have written novels in which criminals are shown to be actual, thinking human beings with feelings and motivations, rather than just vicious animals. Having read Woodworth’s The Holiday Book, I don’t doubt at all that Woodworth would have been horrified beyond all measure at the thought of a person who does one bad thing not being portrayed as doing all bad things all the time. He also wrote about mysticism, spiritualism, and science fiction. Zanoni, for example, is about an immortal Rosicrucian (coincidentally also named Zanoni). So, maybe F. C. W. had issues with seances and immortality.

and wrote about it in terms no less explicit than I just did. He also engaged in quite a lot of it, including (so stories go) with over 200 different women on 200 consecutive nights, at least one or two women married to men who were not Lord Byron, possibly a sister-in-law, and maybe a choirboy. I guess Byron checks all three of F. C. W.’s boxes: a heart blackened with vice ☑, impurity ☑, and debauchery ☑. Why Bulwer-Lytton, though? Sure, he gave us “It was a dark and stormy night,” but that gave us the Bulwer-Lytton Fiction Contest. Also, he may be in part responsible for the fact that formal wear for men is typically black in the US and UK. But are purple prose and black tuxedoes really enough to condemn Bulwer-Lytton? Well, he might also have written novels in which criminals are shown to be actual, thinking human beings with feelings and motivations, rather than just vicious animals. Having read Woodworth’s The Holiday Book, I don’t doubt at all that Woodworth would have been horrified beyond all measure at the thought of a person who does one bad thing not being portrayed as doing all bad things all the time. He also wrote about mysticism, spiritualism, and science fiction. Zanoni, for example, is about an immortal Rosicrucian (coincidentally also named Zanoni). So, maybe F. C. W. had issues with seances and immortality.

Also, Edward Bulwer-Lytton tended to handle criticism about as well as Coleridge (and he even had some nasty things to say about The Edinburg Review!), although Bulwer-Lytton tended to have much more public fits of outrage. Rather than giving a speech in which he blamed novels for false criticism, he would write and publish pamphlets describing how awful the people who disliked his novels really were. He did far more than his fair share to shore up the scandal sheet market. Also, he was for many years in involved in a particularly bitter, long-running breakup/divorce/land war in Asia with Lady Rosina Bulwer Lytton. It started in 1833 and continued until both Bulwer-Lytton and Bulwer Lytton were dead. Both Edward and Rosina seemed to enjoy tearing each other down, and in 1858 he managed to have her detained in an asylum for a short while. She managed to thoroughly destroy any hopes he had of a political career, accusing him of, among other things, murder, incest, and sodomy. Of course, most of the really brutal stuff between them happened after F. C. W.’s letters to The Mother’s Magazaine, so I’m fairly sure F. C. W. can’t count false imprisonment against Bulwer-Lytton (and I’m not sure he would count that as a bad thing in any case). But I do mention this for a reason, and I’ll get back to it later.

One other thing I should mention about both Byron and Bulwer-Lytton was that, from time to time, they supported modern ideas (you know, for the 19th century). Byron, for example, spoke out against state-sponsored religion and supported the Luddites (or at least opposed the death penalty for some of their actions). Bulwer-Lytton, in 1832, wrote a review of a volume of poetry in The New Monthly Magazine in which he argued that women should be educated just as men are. Don’t get too excited, though.

One among the designs in the ambition entertained by the present conductors of this Magazine, is to support that wise and enlarged social policy which would give to one sex the same mental cultivation as to the other. Of all cant in this most canting country, no species is at once more paltry and more dangerous than that which has been made the instrument of decrying female accomplishment. All that execrable twaddle about feminine retirement, and feminine ignorance, which we are doomed so often to hear, has done more towards making women scolds, and flirts, and scandal-mongers than people are well aware of. All minds, whether of males or females, that are ignorant and empty, can only find delight and occupation in a small circle.

In case you follow his line of reasoning and start to worry that it might have some classist implications, don’t worry. He totally spells them out for us. But, I guess he’s at least trying to argue that educating everyone is good. A few paragraphs later, he says something that sounds very modern, though.

Thinking, then, that it is so necessary for all who are actuated by the high and pure desire to reform and liberalise our social system, no less than our legislative, to encourage rather than (as hitherto Englishmen have done) dampen and satirise that ambition which directs women to intellectual cultivation and mental eminence, we are disposed, in our capacity of critics, to pay particular attention to those works which emanate from the gentler sex.

That sort of reminds me of Lilit Marcus’s “Why I Only Read Books by Women in 2013” and the shitstorm from men that followed. Of course, since one of Bulwer-Lytton’s tactics to get back at critics was to take over editorship of a journal and use it to attack his enemies and show how cool he was, I also can’t help think of Jia Tolentino’s “Damn, You’re Not Reading Any Books by White Men This Year? That’s So Freakin Brave and Cool”.

In the same review, Bulwer-Lytton also wrote, “Women can neither jostle us in our political career, nor thwart us in our vainer and more alluring ambitions of society.” Again, this was 1832, some years before his wife managed to jostle his political career to death.

Given the way people react in 2016 to someone saying, “I’m going to try to read more books by people who aren’t white men,” I suspect F. C. W. could have put Bulwer-Lytton high on his list of people whose hearts are blackened with vice, impurity, and debauchery. But, just in case that review and his novels weren’t enough, Bulwer-Lytton was a member of the British upper class yet supported the Reform Bill, which limited the power of the elite in elections. His novels mocked rival politicians, did not always show Christians as in all ways perfectly good and pagans as in all ways perfectly evil, and did not show social standing as equivalent to moral value. Remember, most of the people we’ve seen so far who objected to novels on moral grounds ultimately objected to them because they would lead to dissatisfaction with the current, and massively unfair, social order. When complaining about novels is the hardest work you have to do in an average week, you are exactly the kind of person who stands to lose a lot from social reform.

Of course, no matter what F. C. W.’s actual reason, I can’t take his criticism too seriously. The first article in volume IV of Woodworth’s Youth’s Cabinet specifically mentions Bulwer-Lytton and his novel The Last Days of Pompeii, as though all reasonable ten-year-olds can be expected to have read it. Volume IV came out in 1853, which is before Bulwer-Lytton tried to have his wife committed but well after their post-breakup spat had begun. There isn’t any particular reason that Bulwer-Lytton would have redeemed himself in Woodworth’s eyes, except that possibly as he aged, he grew less overtly liberal. It looks like Woodworth wasn’t particularly consistent in his views on morality. Just as Bulwer was bad yesterday but good today, so was drinking. In The Holiday Book, drinking alcohol means you lose an arm, and nobody really feels sorry for you. It’s just what you deserve for drinking alcohol. Meanwhile, in Wonders of the Insect World, he finds drunk bees (and drunk people) to be more silly than anything else.

His second letter, also titled “Moral Poisons,” was published just over a year later. It was a rant against anything all forms of literature that question his favorite version of religion, or, as he says, “strike the axe at the root of the religion of the Gospel.” Honestly, those other writers who want to strike the axe at the root of the religion of the Gospel are late to the party. St. Paul got there way before them.

This letter starts out pretty disappointingly. If you’ve heard a television preacher, you’ve read F. C. W.’s first page. Then we get this:

I know a young man–it was but a few weeks since I received a letter from him full of bitter lamentations respecting his spiritual state–whose early education had been under the happiest influence, who was blessed with the counsels of a godly mother, and the advantages of an efficient Sabbath school instruction, but who, in an evil hour, received the germ of scepticism into his mind through the pages of Voltaire and Tom Paine. He has long since repented that he ever came in contact with these contagious principles, but his repentance came too late. “Oh,” he says, “Oh, that I might break loose from their influence! But alas! I cannot, I cannot!” He has enjoyed several seasons of religious revival; but the Spirit passed him by unblest. So strong and abiding is the contrary agency of scepticism–so virulent is the action of the infection–that a vitiated tone has been imparted to his moral sentiments, which the reason and judgment cannot correct or control.

Yes! It’s another fake note from a fake victim of dangerous books that the author just happened to stumble upon as he was writing his own letter. Also, he has chosen to pick on Thomas Paine and Voltaire, two people he was ill equipped to cross words with even though both of them were dead. Honestly, I think his second “Moral Poisons” would have worked a lot better if he had ignored Voltaire and Paine and the rest of his nonsense and instead spent most of his energy expanding the fake note from his fake friend. I give it two stars out of five. Still better than Highlander 2, though.

As a side note, it’s kind of sad to read this and realize that, back in the day, Voltaire and Paine were some of the big name skeptics, while now we’ve got Penn Jillette, Richard Dawkins, Sam Harris, and a bunch of angry white teenagers who are just about qualified to go toe to toe with folks in favor of astrology and homeopathy in the comments section on YouTube. That’s not to say there aren’t a bunch of competent, intelligent, scientifically educated, decent human beings who are neither white supremacists nor misogynists in the skeptic movement, but damn, folks, get it together.

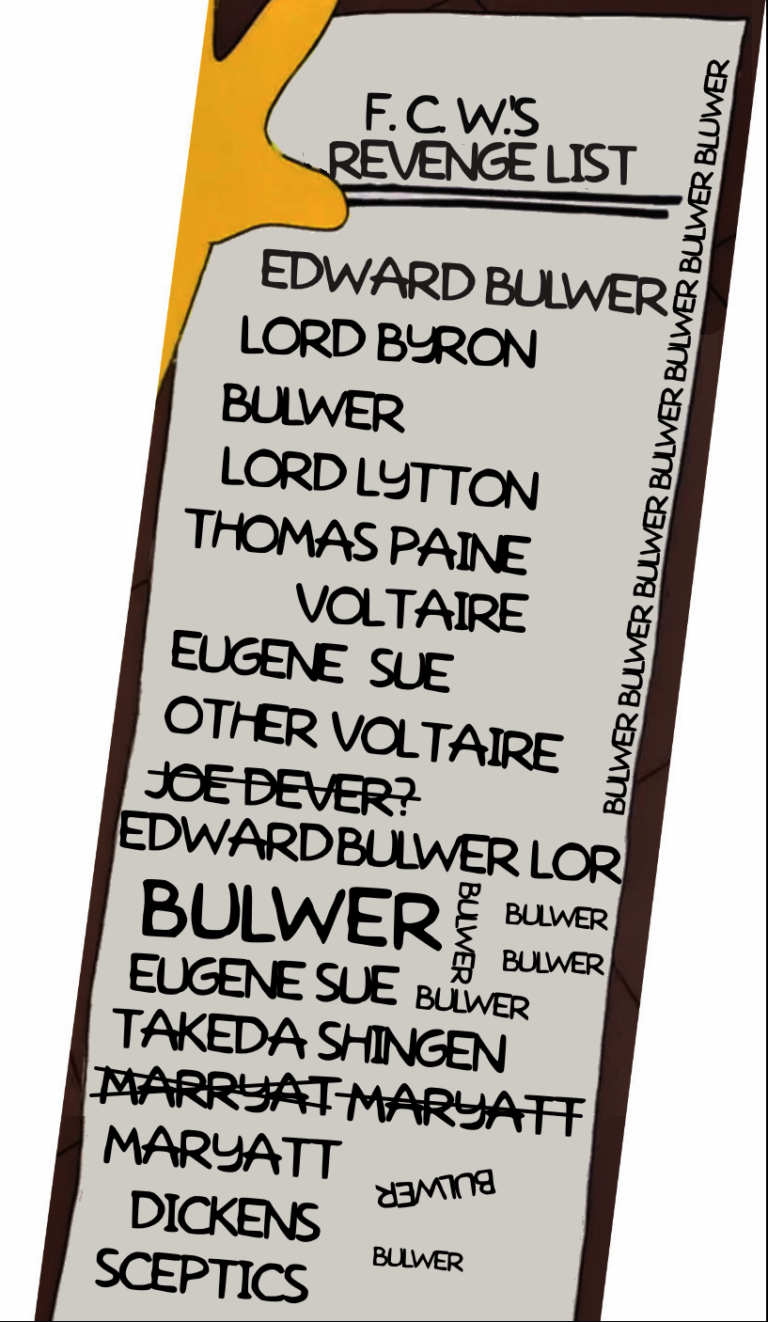

“Who Write Our Novels?“, his third letter (as far as I can tell, at least, not having access to the full run of The Mother’s Magazine), is really “F. C. W.’s Revenge List,” and I’ll bet you can guess who he starts with! That’s right, Bulwer! Is it just me, or do you also think that F. C. would have said “Bulwer” just like John Scalzi says “Scalzi” in the audiobook of the fantastic short story “John Scalzi Is Not A Very Popular Author And I Myself Am Quite Popular“? So, Bulwer… Lots of reasonable Christians like him, says F. C., but did you know that if you talk to the only person in the world who hates Bulwer-Lytton more than F. C. W. (and that’s his ex-wife, Rosina Bulwer Lytton), you’ll hear some truly awful things about him? Look, nobody is actually going to argue that Bulwer-Lytton wasn’t an awful person to live with, or that he never did any truly awful things to Bulwer Lytton, but asking her if Edward Bulwer-Lytton is a good person is like asking Donald Trump if any good human beings live in Mexico or if Hillary Clinton can find her backside with both hands. Or like asking Donald Trump anything, really. Don’t do it. You won’t learn anything useful, other than that either Bulwer Lytton hadn’t reached the stage where she accused her husband of sodomy and murder, or F. C. W. wasn’t willing to repeat such an accusation.

The second person on F. C.’s list is Eugène Sue, a French author who inspired a lot of American authors in the 1840s. One of Sue’s most popular works, which was extremely popular in the United States and which F. C. W. calls out by name, is The Mysteries of Paris, about the seamy underbelly of Paris. It was published in a series of 150 chapters in a major, politically conservative French newspaper from 1842 to 1843. Sue apparently started writing The Mysteries of Paris so that it was as sensational as it could be, and since he was in France, that was way more sensational than it would have been in the US or the UK. However, once he started hearing from people who felt sympathy for the criminals in the story, or who recognized their own unfortunate situations in his work, he started including more social themes. It’s hard to tell whether the sexuality or the eventual turn toward socialism more troubled F. C. W. What F. C. does tell us, though, is that American author N. P. Willis disliked Sue: “Hear the testimony of N. P. Willis respecting him: ‘When I visited him ten years ago, he was an elegant voluptuary of the first water. He is by this time sloped from his meridian, and apparently turning his experience into commodity.’ So it would seem; for while the ‘Mysteries of Paris’ were in course of publication, the police of that city arrested the author, on the ground that the scenes of the book were to licentious for Frenchmen”. Let’s start with the second charge, that Sue was arrested for writing smut. Sue was arrested, but not while writing a book. He was arrested several years after F. C. W.’s last cranky letter to The Mother’s Magazine, during Napoleon III’s 1851 coup. According to Victor Hugo, he demanded to be taken into custody when he encountered soldiers arresting other political bigwigs. But that’s it. I can’t find any mention of Sue being arrested while writing The Mysteries of Paris, so I assume F. C. W. made it up. He did not make up N. P. Willis’ claim, but we should probably look at the rest of what Willis actually said. It’s from a piece he wrote for newspapers. It covers a lot of topics, so I’m going to quote the sections that actually relate to Sue.

Ten thousand copies of the “Mysteries of Paris” have been poured into our cauldron of morals by a single press in this city, and probably fifty thousand will be circulated altogether. It is a very exciting book, and at this moment making a great noise. The translators are busily at work on other saleables of French literature, and there will soon be little left unknown of the arcana of vice. Eugene Sue, the author of the “Mysteries of Paris,” is a connoisseur of pleasure, and when I last saw him, ten years ago, was an elegant voluptuary of the first water. He was just then creeping through the crust of the Chaussée d’Antin into the more exclusive sphere of the Fauborg St. Germain–fat, good-looking, and thirty-two. He is, by this time, “sloped” from his meridian, and apparently turning his experiences into commodity. I observe that he borrows my name for a wicked Florida planter who misuses a lady of color–a reproach which I trust will not stick to “us.”

The publishers hang back from American fiction now-a-days, possibly finding the attention of the reading public occupied with the more highly-spiced productions of the class just alluded to, and it is impossible to induce them to give anything for–hardly, indeed, to look at–an indigenous manuscript. Accident threw into my hands, a few days ago, a novel which had lain for some time unread in a publisher’s drawer, and after reading a few chapters I became convinced that it was far above the average of modern English novels, and every way worthy of publication. It was entitled “The Domine’s Daughter,” by Adam Mundiver, Esq., and would have lain forgotten an unexamined until doomsday, but for a friendly Orpheus who made it his Eurydice and went to Lethe after it. Such a book should surely represent money in a country where literature is acknowledged.

In other words, N. P. Willis was sick of French literature being published in America, and he sounds a lot like a spoiled, untalented white guy complaining about affirmative action and how it’s impossible for him to get a job. This is exactly the kind of guy I’d pick if I only had a paragraph to justify my hatred of Eugène Sue, assuming my plan was to guarantee that nobody would take my argument seriously. Just to sum up, the only evidence F. C. W. has been able to provide for his condemnation of Bulwer-Lytton and Sue comes from two of the least reliable people I can think of (plus one flat-out lie that F. C. probably made up on the spot). Bulwer-Lytton’s private life was, in fact, a train wreck, assuming the trains involved were loaded with flaming dumpsters, and assuming that the wreck blocked the road so that three busloads of Trump supporters were just wandering around with nothing to do. I’m not sure about Sue, but it sounds like he may have gotten up to one or two things in his youth, too. Finding bad things to say about them should not be this hard, so I think it really says something about F. C. W. that he screwed that up so spectacularly.

As far as I can tell, The Domine’s Daugher never did get published.

Let’s check our scoreboard to see how F. C. W. is doing.

| Stock Attack | Used? |

|---|---|

| Stimulation of violence, sadism, and criminality | ❌ |

| Undermining of sexual morality and legitimate authority | ✅ |

| Promotion of passivity through narcotization, hypnosis, and desensitization | ❌ |

| Substitution of fantasy for reality; promotion of escapism | ✅ |

| Promotion of stereotypy, distortion, oversimplification, and irrelevance | ❌ |

| Deliberate emotional manipulation and exploitation of consumers | ❌ |

| Destruction of literacy | ❌ |

| Weakening of family ties | ✅ |

| Destruction of artistic integrity and creativity in society | ❌ |

| Homogenization of culture at the lowest level | ❌ |

| Promotion of materialism and conformity | ✅ |

| Making readers less intelligent | ❌ |

| Posing an actual physical risk to health | ❌ |

| Being addictive in the same way that drugs or alcohol are | ❌ |

| Being metaphorically (or literally) infectious, toxic, or venomous | ✅ |

| Causing the end of some mythical golden age, or at least reminding us of its end | ❌ |

| Being fun or pleasant, since nothing fun or pleasant can be good for you | ❌ |

| Total: | 5 |

We’re three letters to the editor in, F.C.W. has only come up with two titles, and he has managed to make a total of five rather trite points. That’s at least an average of more than one per letter. Let’s see if he can can do better next time. I try not to spend two posts on any one cranky old codger, but this guy was just so busy and attacked so many people that I just had to share it all with you. I’ll make it up to you, though. Next time there will be footnotes, plus a quick and entirely uninformed analysis of how none of the people who hate novels can really agree on which novels are bad. Also, we’ll see some evidence to suggest that F. C. W. is really F. C. Woodworth.